Does hearing about pesticides on produce make people less likely to eat fruits and vegetables? No – just the opposite. But that’s what the pesticide lobby would like to have you believe.

With the release last week of EWG’s annual Dirty Dozen™ list, pesticide interests are once again falsely claiming that our ranking of produce with the most pesticide residues, as detected by 36,000 U.S. Department of Agriculture tests, will scare Americans away from healthy diets.

This comes despite the fact that we say it's essential to eat plenty of fruits and vegetables, whether they're grown organically or conventionally. What’s more, research paid for by pesticide interests shows that hearing about EWG’s Shopper's Guide to Pesticides in Produce™ makes most people more likely to buy fruits and vegetables.

Unfortunately, some reporters didn’t look closely at the research and bought into the industry’s “alternative facts.”

- On Jan. 18, The Washington Post reported: “Researchers ... wanted to know how the [Dirty Dozen] list influences our buying habits. They surveyed more than 500 low-income shoppers ... [and] found that specifically naming the “Dirty Dozen” resulted in shoppers being less likely to buy any vegetables and fruit.”

- On March 9, a Bloomberg newswire report on the same study said: “In response to several statements about the differences between organic and conventional fruits and vegetables ... the statement citing the Dirty Dozen list ‘elicited the greatest number of people to choose ‘less likely’ to purchase any type of fruits or vegetables.’”

- On March 12, a columnist for Food Safety News wrote that the Alliance for Food and Farming, a perennial critic of the Dirty Dozen “made hay [by] citing a study that showed low-income people interpret information about pesticide residue as meaning they should avoid all fruits and vegetables.”

Neither the freelance author of the Post story nor the Food Safety News columnist called EWG to get our take on the study. The Bloomberg staff reporter did call us and included some of our reasoning behind the Dirty Dozen, but not our response to the study. And none of the three reports mentioned that the study was funded at least in part by the Alliance for Food and Farming.

The Alliance, or AFF, operates out of a post office box in Watsonville, Calif. – the heart of an agricultural region where conventional strawberries are grown with some of the heaviest doses of neurotoxic pesticides in the world. (Perhaps it’s no coincidence that conventionally grown strawberries topped the Dirty Dozen list for the second straight year.)

The list of AFF’s funders reads like a Who’s Who of chemical agribusiness groups. AFF says it “exists to deliver credible information to consumers about the safety of fruits and vegetables.” But its most visible work has been attacking EWG. In 2010, AFF received $180,000 in federal taxpayer money from the USDA specifically to mount a PR offensive against the Shopper’s Guide.

Last year AFF commissioned three researchers at the Institute for Food Safety and Health at the Illinois Institute of Technology to conduct a study that surveyed low-income shoppers in the Chicago area to find out if hearing information about pesticides on fruits and vegetables had any affect on their plans to purchase produce in the future.

Researchers asked 618 shoppers dozens of questions about their shopping habits, and identified some clear barriers to purchasing fruits and vegetables, including cost and availability. Participants heard seven messages about pesticides on produce, then were asked if the statements made them more or less likely to buy fruits and vegetables, or made no difference.

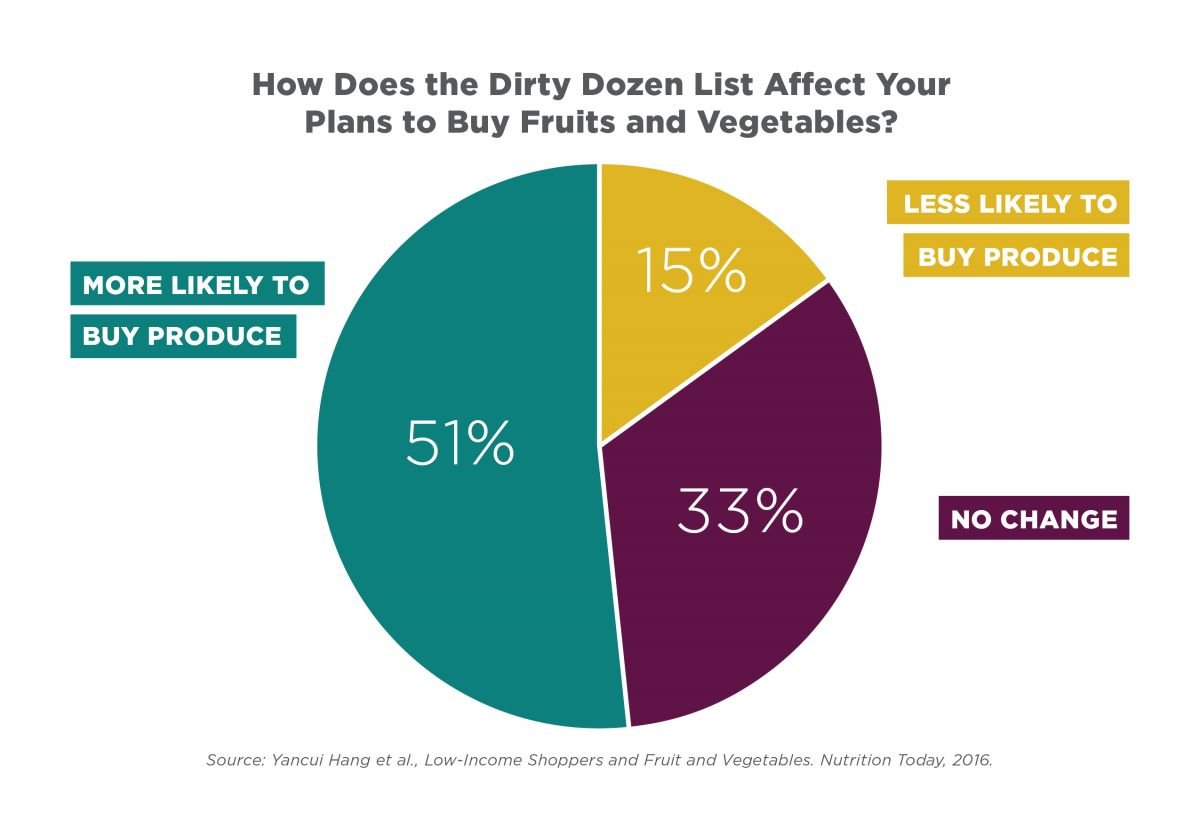

One of the messages specifically cited the Dirty Dozen list, saying: “An environmentalist group called the Environmental Working Group has developed a list of the 12 fresh fruits and vegetables they say have the highest pesticide levels on average ... They suggest that it is best to buy these fruits and vegetables organically grown.” (Our emphasis added – the phrasing fails to point out that our list is based on USDA data.) Here’s what shoppers responded:

As you can see, slightly more than half of the respondents said the Dirty Dozen list made them more likely to buy fruits and vegetables. One-third said the list wouldn't make them change their shopping habits. Only about one in six said the Dirty Dozen list would make them less likely to buy produce.

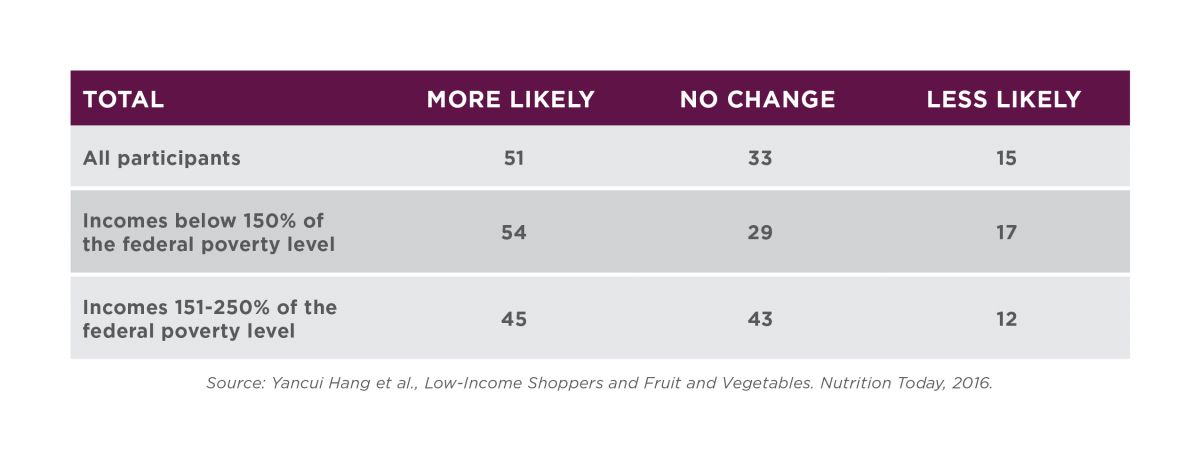

What's more, the table below shows that shoppers with the lowest incomes were slightly more likely than those with relatively higher incomes to be prompted to buy more produce after seeing the Dirty Dozen list.

It’s true – as Bloomberg reported – that of the seven messages read to shoppers, the statement about the Dirty Dozen got the largest percentage of “buy less” responses. But that pales in comparison to the finding that about six times as many shoppers said EWG’s list would either influence them to buy more fruits and vegetables, or make no difference. And that was only in comparison to six other statements, some of them worded to downplay the difference between organic and conventional produce.

The study may be useful to AFF as a marketing tool, but it’s hard to take it seriously as objective research. It simply recorded shoppers’ on-the-spot answers, making no attempt to follow up and learn whether people actually changed their shopping habits for a day, a week or a year after hearing about pesticides on produce. Without that information, you can’t draw any solid conclusions about the relationship between messages about pesticides and the shopping habits of low-income Americans, whose purchasing behaviors are guided by myriad variables.

Hoping to find out more about the study, EWG reached out to Dr. Britt Burton-Freeman, who is listed as the corresponding author. We asked how much money AFF gave for the study and whether AFF directed researchers to ask specifically about the Dirty Dozen. She did not respond to an email or a follow-up phone call.

Unlike the single-issue agenda of AFF, EWG addresses a broad spectrum of issues related to both organic and conventional foods.

- We’re working to boost organic production, permanently restrict the use of the most toxic insecticides on the food you eat, and educate the public about the importance of fruit and vegetable consumption, as well as which produce has the most pesticide residues.

- Poverty, food security and food access are huge problems in the United States. We are supporting the SNAP program, fighting for more nutritious food in American school lunch programs and providing people with tips about eating healthy on a tight budget.

- We’ve also just launched our Plate of the Union campaign. It aims to awaken a new audience of American consumers to become activists for policies that make food safer, make healthy food more accessible and make food production better for our environment.