Thousands of gallons of liquid pig feces are sprayed on the field just eight feet from your kitchen window. On many days, you and your family are unable to go outside the house due to the putrid stench: No barbeques, relaxing on the porch with friends and loved ones, or children playing in the yard. The smell from the manure and ammonia plume dangling above your property is so strong it often triggers vomiting, nausea, and lung and eye irritation. The tap water could very well contain traces of the offending and dangerous swine waste, too, forcing you to buy and drink bottled water. The waste saturates your property and builds up along the exterior of the house, attracting droves of flies, mosquitos, rats and snakes.

Depression sets in as you and your family face the fact you’ve become prisoners in your own home: A home you own, pay taxes on, and had hoped would be a safe and comfortable place to live, raise a family and grow old in. This is a slice of the American dream turned into a nightmare, courtesy of the industrial swine operation that borders your property.

Welcome to life alongside a factory farm.

This is the reality of Elsie Herring of Duplin County, N.C., and tens of thousands of other Americans in this state, Iowa, Indiana, Colorado, Missouri and beyond.

Elsie Herring: Part II from Powering a Nation on Vimeo. Produced as part of Whole Hog, a journalistic project of UNC Chapel Hill School of Media and Journalism

Herring’s family has owned the land her home sits on for more than 100 years.

“You can smell the odor inside,” Herring recently told Civil Eats’ Christina Cooke. “The feces, the ammonia – all that stuff – we have to breathe it in, because we have to breathe.”

The open-air manure pits, which the pork industry affectionately calls “lagoons,” can stretch the length of several football fields, and there often are multiple pits on each hog farm.

A big hog operation can produce as much waste as a medium-sized city, and a handful of rural counties in North Carolina can generate more excrement per year than New York City. EWG and Waterkeeper Alliance estimate that North Carolina’s multi-billion-dollar pork, poultry and beef industries produce enough fecal waste to top off 15,000 Olympic-size swimming pools.

“The pit will fill up, so it has to be emptied,” said Steve Wing, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Public Health, in an interview for the documentary, “Speciesism: The Movie.” The pits are emptied by spraying liquid waste into the air, which then drifts into the neighboring communities, Wing added.

This includes neighborhoods like Herring’s.

In a separate interview for the documentary, Herring noted that when the feces spray hoses fire up at the Smithfield Foods hog operation adjacent to her home, “you think it’s raining.” The misty manure fills the air and falls on her, the house and her laundry drying on the line. Even with the windows and doors shut, the acrid odor fills the air inside her house, Herring said.

Source: Species: The Movie

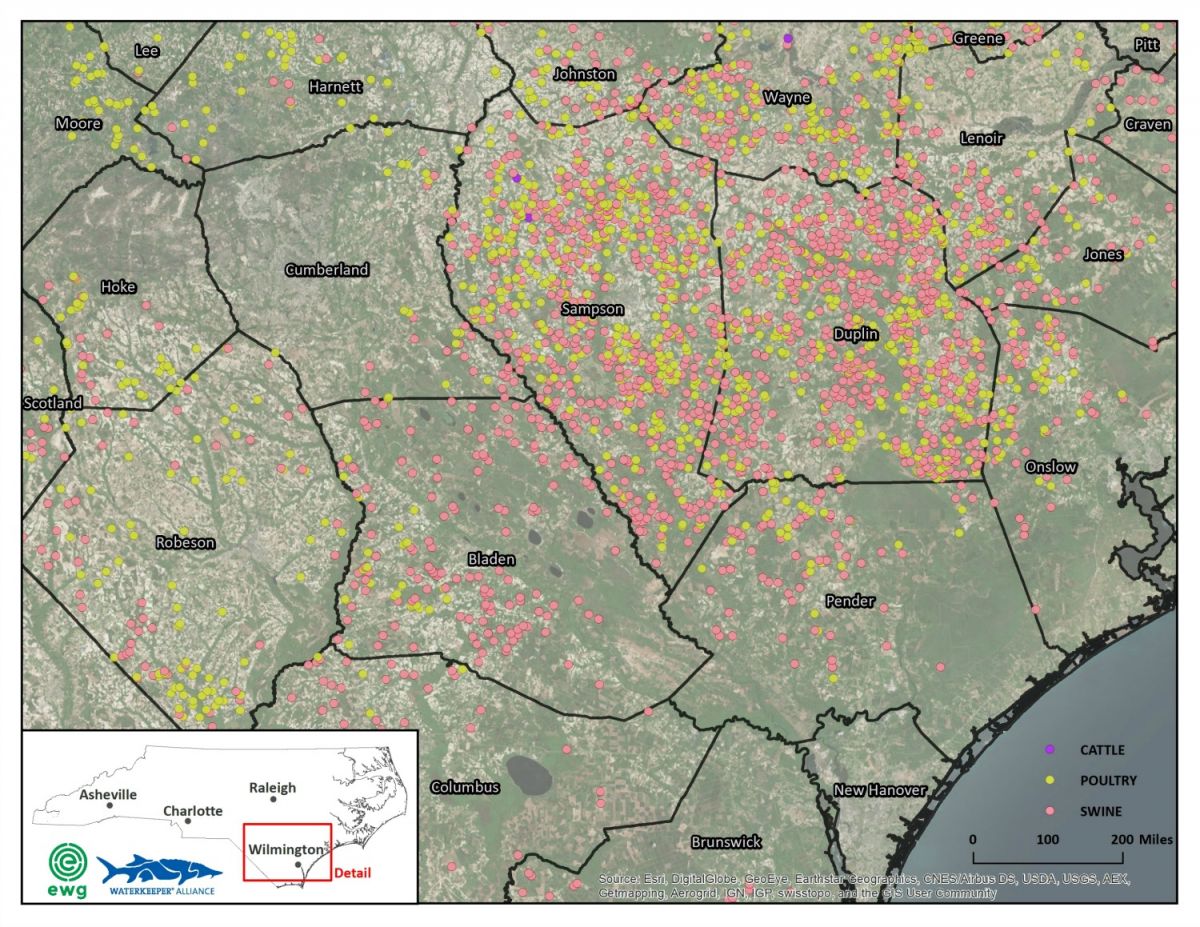

A new report by EWG and Waterkeeper Alliance found more than 4,100 of these waste pits in North Carolina – second only to Iowa in industrial hog production.

Of course, it is not just excrement and urine that spills from the confined animal barns into the open-air cesspools. Large pork operations, like the one bordering Herring’s home, use every technology possible to grow pigs as fat and as fast as possible. Factory hogs are fed antibiotics and injected with various vaccines to keep them alive in an insufferable environment, hovering near 100 degrees Fahrenheit inside the barn with stifling chemical-filled air, which is released through a whirling ventilation system and sent into the air of the adjacent hamlets. Insecticides are regularly sprayed on the pigs, too. These compounds, along with manure, afterbirth, blood, nitrogen, chemicals and other nasty, toxic waste, fill the pits and can ooze into groundwater and permeate the air. The waste is sprayed on farm fields alongside places where people live, worship and go to school.

A number of studies have shown that pollution from concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, like those in North Carolina, can elevate the risks for respiratory problems and blood pressure for those who live and work near the operations. Another study, led by Wing, found increased prevalence of asthma symptoms for North Carolina children who go to schools near pig farms. Deadly pathogens, including salmonella and E. coli, breed from the manure pits, too, and can spread through water and air. The federal Environmental Protection Agency estimates that in 2014, more than 421 miles of North Carolina rivers and streams were “threatened or impaired” from “fecal coliform.”

Some workers who maintain the cesspools have died after being overcome by noxious fumes. Last July, a father and son both died from gases they inhaled while tending to the pit on their swine farm in Cylinder, Iowa. The same month, a father and son were killed in Wisconsin after being consumed by the fumes emanating from a hog manure pit.

The epicenter for industrial hog production in the U.S. is packed into two counties in the Tar Heel state: Duplin and Sampson. These two rural, poor and largely African-American communities produce roughly 40 percent of all the wet animal waste in the state, according to the EWG-Waterkeeper analysis. A sweeping 2008 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office estimated that swine operations in just five North Carolina counties, including Duplin and Sampson, generated more than 15.5 million tons of waste in one year.

According to an analysis of federal and state records by Waterkeeper Alliance researchers, only 12 of the 2,246 swine CAFOs in North Carolina have been required to obtain permits under the federal Clean Water Act. The remaining 2,234 hog farms are free to operate under the state’s far less stringent permitting requirements, which assume all farm pollution is controlled and contained by the corporations that own and operate them.

In 2015, the U.S. EPA’s Office of Civil Rights agreed to investigate North Carolina’s lax oversight of the hog industry and whether it disproportionately impacts the African-American populations comprising much of the communities near factory farms.

The investigation came after the federal agency was petitioned by the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network, Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help and Waterkeeper Alliance. EarthJustice and the University of North Carolina’s Center for Civil Rights are co-counsel on behalf of the groups.

Nuzzled near the Atlantic coast, these counties are beset with numerous air and water quality problems. In a scathing Rolling Stone profile of Smithfield Foods and its operations in North Carolina published in December 2006, it was noted that, “in North Carolina alone [Smithfield has] spilled, in a span of four years, 2 million gallons of shit into the Cape Fear River, 1.5 million gallons into its Persimmon Branch, one million gallons in the Trent River and 200,000 gallons into Turkey Creek.”

When heavy rains hit, the manure pits can easily overflow, spewing the fecal mess into rivers, streams and lakes, and ultimately drinking water. EWG and Waterkeeper Alliance found at least 170 of these waste pits within North Carolina’s 100-year floodplain, putting communities in the southeast portion of the state at risk should an epic storm, like a hurricane, hit.

Oh wait, that already happened.

The deluge brought on by Hurricane Floyd in 1999 created an environmental and public health crisis for coastal North Carolina as the open-air pits, already brimming with toxic fecal matter, spilled out and into waterways and ultimately arrived at the ocean where a dead zone formed. It killed millions of fish and other sea creatures. It is estimated that between 100,000 and 500,000 hogs drowned in the storm as well, with many of the carcasses floating into streams and rivers, along with the waste, through the watershed and into the ocean. There were even reports of sharks devouring the dead pigs.

Federal and state authorities, as well as the hog industry, pledged to take steps to make sure that never happens again. But, as headlines were forgotten and the impacts of the hurricane faded, efforts to protect the environment and the people of the region waned.

Since 1999, the state government did manage to de-commission some waste pits within the floodplain, but funding eventually dried up. As the EWG-Waterkeeper map shows, there are at least 170 open-air manure pits still inside the floodplain, just as they were before Hurricane Floyd bore down on them and opened the feces floodgates.

Most Americans are not directly impacted by the public health threat these factory farms present. We stand outside our homes knowing a cloud of manure mist won’t waft through the evening air, forcing us to shut ourselves inside until it passes. Our clothes don’t reek of pig poop, and our local drinking water sources are not under constant threat.

Elsie Herring: Part III from Powering a Nation on Vimeo. Produced as part of Whole Hog, a journalistic project of UNC Chapel Hill School of Media and Journalism

But for communities like the one Herring calls home, the direction of the wind can determine if people can be outside at all.